A Systems View of the Space

In recent years, the AI landscape has fanned into a spectrum, with model builders on one end and system builders on the other. This dynamic echoes that of the early 2000s, when statistical models began to displace expert systems and the focus shifted from engineering structures to learning patterns. With the rise of LLM systems, that shift is reversing: focus has broadened beyond models alone, as the surrounding structures have come back into view.

From Expert Systems to LLM Systems

Early on, the dominant view was that intelligence could be explicitly represented by systems that encoded human expertise into symbolic rules. These expert systems relied on a narrow, logical toolkit, making them precise but brittle and difficult to construct. Over time, the field turned to learning patterns rather than defining them. Statistical models (and later deep learning) proved that generalization from data could outperform handcrafted logic across a wide range of tasks. Transformers broadened this generalizability through large-scale pretraining.

With the introduction of LLMs, the prevailing intuition is once again evolving. Language itself has become a substrate for directly shaping model behavior, expanding a previously brittle expert systems toolkit to include higher-order behaviors like reasoning, decomposition, reflection, and more. LLM systems blend prior paradigms by layering an expanded systematic toolkit onto a generally intelligent backdrop. The result is a set of capabilities more flexible, adaptive, and nuanced than either paradigm alone.

A Recent History of LLM Systems: “GPT-3 content sucks - ALL. OF. IT”

The picture we see today wasn’t obvious initially. LLMs like GPT-3 presented as promising but unreliable text generators, and public sentiment unsurprisingly focused on their limitations:

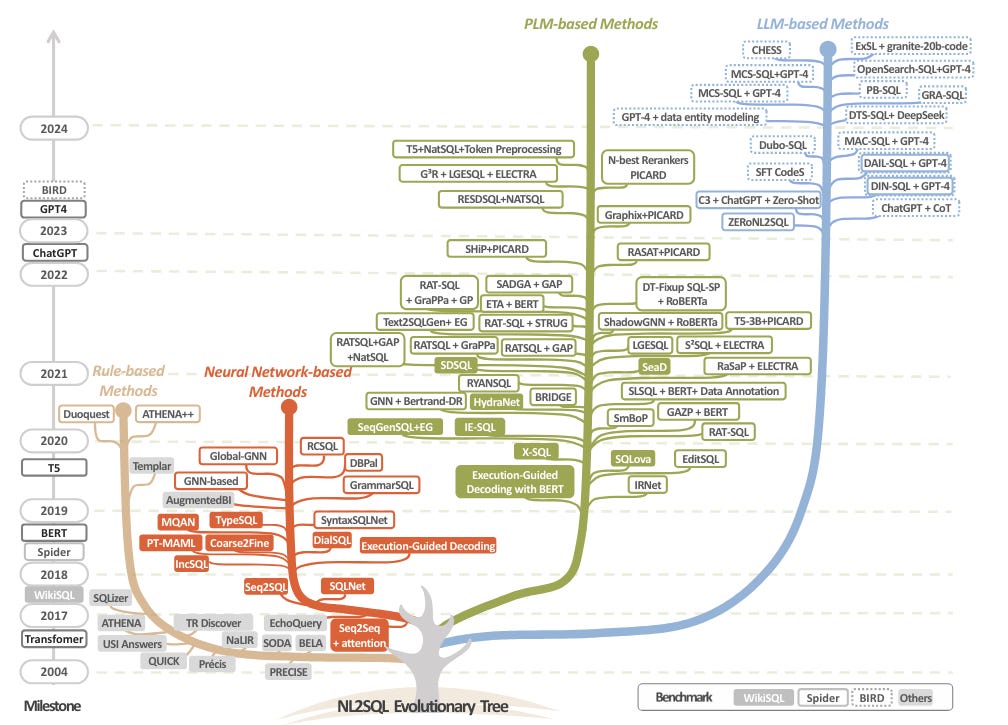

But the potential of the natural language interface quickly became clear, as meaningful gains could be had through simple prompting tricks alone:

The realization that language could act as a source of leverage was a clear inflection point. Techniques like chain-of-thought and directional stimulus prompting were quickly formalized, and the practice of prompt engineering—leveraging model malleability—came into view.

Shortly afterward, another realization naturally emerged: knowledge not included in model pretraining could be provided directly through context. In-context learning enabled outcomes that these models alone could not come to. Layering prompt-engineering techniques on top of this injected context further improved the models’ ability to reason over new information.

After prompt-engineering and in-context learning, the field moved to composition. Given their malleability, models could be shaped into specialized components whose interactions exploit underlying asymmetries—boosting performance whether the relevant knowledge was parametric or had to be supplied through context. Techniques like best-of-N sampling pointed at the generation-verification gap, hierarchical decomposition at the planning-execution gap. Not long after, these techniques were organized into structured pipelines—referred to initially as chains, then workflows, then compound AI systems. Although terminology shifted (and continues to), the core idea holds: compositional structures can exploit imbalances to exceed the performance of a single raw model call alone.

Over time, state-sensitive, closed-loop controls like ReAct were introduced into these workflows—agentic components. More and more components of these workflows gained autonomy and state awareness, eventually leading to workflows made entirely of agentic blocks. Systems have most recently shifted towards global autonomy, with agents constructing their own pipelines by selecting tools, organizing subagents, and retrieving relevant context. But several outstanding gaps remain including reliable self-evaluation, environmental exploration, and objective drift. This emerging practice—architectural discovery and self-construction—marks a key frontier in LLM system design, in which workflows are set aside for entirely autonomous agents.

Future Directions: System Discovery,

Self-Construction, and Self-Improvement

Taken together, this recent history marks a shift from single‑call prompts to structured workflows to self‑directed agents. To date, this autonomy has largely been directed toward utility: how do we discover and self-construct architectures that accomplish the task at hand?

At Distyl, we partner with enterprises to solve their most ambitious problems. Systems in these settings cannot simply clear the “utility” bar. They must operate at or near state-of-the-art levels to earn trust, integrate into real workflows, and survive production considerations. Ask your favorite coding agent to produce a conversational system, a text-to-SQL engine, a digital twin—would you deploy it into production out-of-the-box?

For that reason, our goal is to redirect that autonomy toward mastery: how do we discover and self-construct systems that don’t just work, but operate at or beyond state-of-the-art? By focusing on the core challenges of system discovery, system self‑construction, and system self‑improvement (in the context of production‑grade enterprise AI systems), we believe we can collapse the time required to produce state‑of‑the‑art systems from months to minutes.

System Discovery

System discovery searches for opportunities to drive impact within an enterprise and proposes associated architectures. In the scientific discovery world, this maps to hypothesis generation and high‑level research planning. Systems like ADAS, AI Co-Scientist, and ResearchAgent already show that agents can propose novel architectures and research ideas outperforming human baselines. While enterprise opportunities benefit from being more bounded than opportunities for novelty in research, they’re also more fragmented and opaque. Processes, data assets, and existing investments are often inaccessible, and even when available, are often buried and hard to find. Progress here rests on piercing through that opacity, and in making well-grounded assumptions when clarity isn’t possible.

System Self-Construction

System self-construction is the process of turning opportunities into production-grade, state-of-the-art systems. In the scientific discovery analogy, this corresponds to self-experimentation: designing experiments, executing them, and properly housing associated artifacts. Recent systems like AutoAgent, AI Scientist, and AI-Researcher show that multi-agent architectures can already translate specifications into functional pipelines with minimal human input. The key challenge on this frontier involves ensuring that self-constructed systems don’t merely satisfy a specification but actively pursue state-of-the-art architectures, iterating toward frontier-level performance rather than freezing at the first functional solution.

System Self-Improvement

System self-improvement targets the painful, iterative process of modifying system scaffolding. This maps to refinement in scientific discovery: iteratively updating the governing model in response to results. STOP, Self-Improving Coding Agent, and Gödel Agent demonstrate that agents can rewrite or augment their own orchestration code and policies to improve performance and/or robustness over time. For enterprises, sometimes objectives are verifiable, but often they are not, and we view self-improvement under non-verifiable conditions as an especially compelling problem space.

Taken together, system discovery, self-construction, and self-improvement form the basis for compounding enterprise transformation. As systems come online, they of course provide value in their isolated scopes. But they also expand the opportunity landscape by feeding their functionality and data products back into system discovery.

On one front is opportunity expansion through utility: systems whose standalone capabilities become functional inputs to system discovery. A maintenance-event classifier, asset-health forecaster, and parts-availability estimator each deliver value on their own, but together they enable a proactive field-service optimizer.

On another front is opportunity expansion through data: systems whose outputs act as data inputs to system discovery. A claims-triage engine producing structured rationales, forecasting model generating risk scores, and routing agent logging decision traces enable downstream systems such as churn prediction and audit automation.

The combination of discovery, self-construction, and self-improvement is not just an efficiency gain—it is an engine enabling transformation.

In the next post, we’ll share our perspective on the bitter lesson—in context of the LLM era—and how we think about these systems in the limit.

If the systems side of the space excites you, or if you vehemently disagree, we’d love to talk. See all available openings here, and feel free to reach out to research@distyl.ai directly with any questions or thoughts.